| Date | 05/26/2023 |

| Time | |

| Location | WdKA |

| Researchers | |

| Affiliated research project |

|

Maike Hemmers presented two projects, the publication “No Kitchen Ever Belongs to Me” and an installation at Kunstinstituut Melly, within the research project Autonomy Lab and the Autonomous Practices study curriculum. The conversation included second year Bachelor students, their teacher Pendar Nabipour, and researcher Natalia Sorzano.

Maike Hemmers is a Rotterdam-based artist whose research reflects on intuitive material relations, shaped by feminism and architecture and what she terms “queer and soft resistance”. She obtained a Master of Fine Art in 2017 from the Dutch Art Institute (DAI).

No Kitchen Ever Belongs to Me

This project was informed by Maike’s interest in a feminist critique of architecture, by looking at architecture as a structure that forms us, influences us, and determines how we are in space. In 2019, she spent some months in De Kiefhoek Museum House located in Feijenoord Rotterdam in 2019. It was built in 1929 by the Dutch De Stijl architect Jacobus Johannes Pieter Oud, as a piece of modernist architecture, for clean, new, and bright ways of living.

Maike wondered, what does it mean for a middle class architect with a higher education to build for the working class. There is a certain distance when one makes something for another community. Today, the museum apartment has kept with the original architecture of 1929 which consisted of a living room downstairs and two bedrooms upstairs, but no bathroom and only a very small kitchen. The kitchen was the most interesting location for Maike. It informed the name of her project which also references a book written by Bernadette Mayer, Utopia, which begins with the sentence “no house ever belongs to me.” In her observation, a lot of the structures that are given to us don’t ever really belong to us, but to the structures that oppress us like capitalism and the patriarchy.

Maike’s challenge was to get in touch with the neighborhood in a way that is interactive and generous with the community. For this purpose, Maike started to make chalk drawings of hands on the ground, as a way of greeting the neighborhood. Through this, she got in touch with children who were outside and ended up drawing together. Drawing became a medium to getting in touch with people. Later, she took the drawings inside, and continued to draw with pastels, the closest material to chalk.

At that time, Maike was reading bell hooks’ book, All About Love that made her wonder how she wanted to live and relate to others, and what it means to work from love.

Through the archive of Het Nieuwe Instituut, she was able to find the original plans of the architect Johannes Pieter Oud. The kitchen of the building was extreme small, with four square meters, which caught her attention. In Oud’s original plan, there was a shower, but it got taken out because it was deemed too expensive for the working class. It was seen as a luxury although the houses were built to provide better conditions for the working class. The kitchen was made small on purpose, because it was deemed improper for people to use their kitchen as a living room. It should not be a place to hang out, but only one for the housewife. Drawers weren’t installed either because the working class was expected to destroy them. Gardens were only put at the back of the house because the working class was considered to be too unruly to maintain gardens that would be visible on the street.

Maike found an article written by Oud called ‘Housewives and Architects’, where he reflected that housewives should be heard in architecture for building middle class homes, because homes are the places they were supposed to occupy in society. But in De Kiefhoek, none of the things he mentioned in the article were actually included in the houses, because he was referring to middle class women. For the working class, women were not supposed to need all those things.

Maike eventually wrote an essay that included all that information and reflected on housing in the South of Rotterdam, including today’s permits that are required in order to be allowed to live in specific locations [according to the so-called Rotterdamwet]. Among others, she looked into a playground where all the seating areas and benches were taken out so that people wouldn’t hang out there. She wondered what our agency is in these spaces that are so determining in shaping behavior. She realized that agency comes in the relationships that are built between people, and between people and spaces; how throughout time, people changed those spaces from within to re-accommodate them to their own needs.

She made drawings in pastels and then flashlight photographs of them in the kitchen to add what she calls “an affective layer”. Through this project, she discovered drawing as a medium to reflect on such topics while having fun and enjoying herself.

In her photographs, she played with layers by stacking them, bending them, and giving them different points of light, so they ended up becoming objects and much more than just drawings. The publication was funded by Woonstad, the housing corporation that manages these houses. Since she knew that Woonstad used to fund art before the financial crisis, she contacted the corporation randomly to see if it would support the project with a little money for the publication. Woonstad said yes, gave her a key to stay in the museum house and €500 to make the publication. It was a good experience for her in just trying to reach out and get support, and to see that it worked. The essay is online so that the work can be widely accessed: https://issuu.com/maikehemmers/docs/mh_nokitchen_digital_single_wimages

Installation at Kunstinstituut Melly

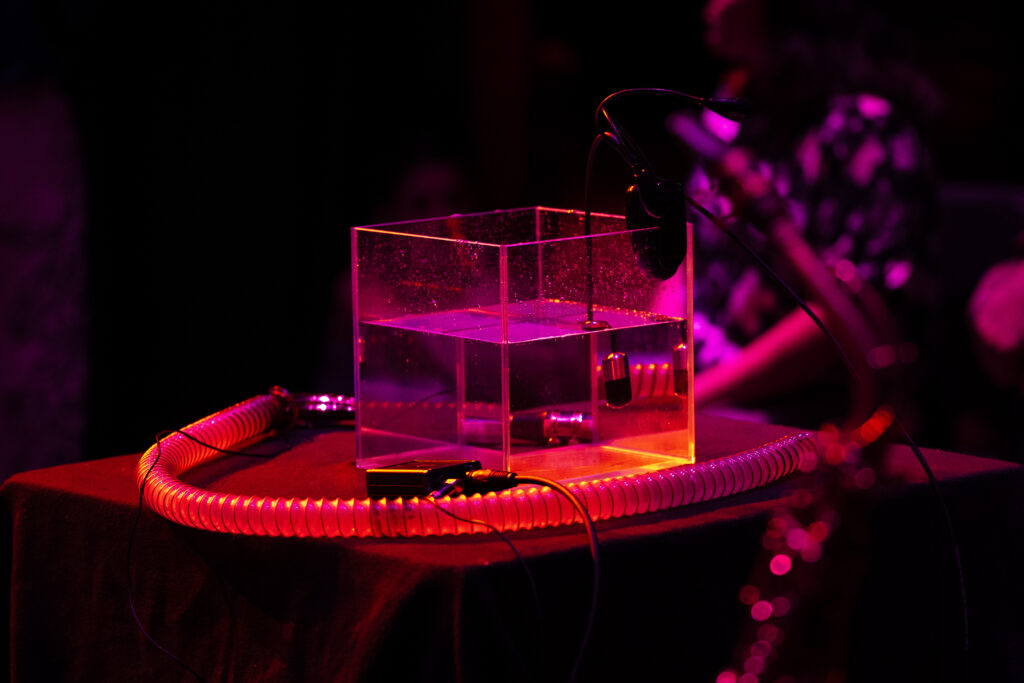

Maike Hemmers was invited to exhibit in Kunstinstituut Melly, based on the aforementioned piece. Maike continued to draw very intuitively and asked herself how can she represent what comes in and out of her. The installation in Melly comprises large format pastel drawings and soft sculptures. She wondered how to provide a structure, form and support to that exploration, and she was looking into somatic and spiritual practices. For this purpose, she worked together with Savannah Theis, who was doing somatic therapy for process work. In process work, you look at individual or collective symptoms. If something comes up, like a headache, then one expands and explores it, by also translating them into movements and sounds. After these sessions Maike would draw her findings. The sculptures made for Melly were developed in cooperation with Savannah and textile designer Karen Huang, who helped her to think about making different objects that could adapt to different bodies, considering the different audiences that could visit the work. They added straps, or slits to fold in different ways, among other techniques to give shape to the objects.

Maike has been working with soft sculptures since 2017. Through these works she wonders what a soft structure or a soft architecture is and can be. She explores with her work what it means to live in structures that are given, that are hard lines that we cannot change, so she asks how can we change them. Her answer is: “by the things we bring inside.”

She dyed the fabrics with natural colors, which was an idea brought by Karen Huang. She mentions that when one works with other people, one also needs to give space for those people to contribute to the work. The choice for natural color dye meant a lot of work, but now Maike is very much into natural color dye. She explains the ratios of natural color dye: One needs a lot of natural materials to get those colors. The measurement is the same weight of the fabric, so 2.5 kilos of fabric require 2.5 kilos of onion skins. At some point she had to go to the supermarkets to get the skin of the onions.

Maike Hemmers defines her work as “being in relation with…” Because her work is so much based on her own subjective experience, it is very important to find moments to open her practice, so that other experiences can come in with collaborations and workshops. She conducted two workshops before the opening of the exhibition at Melly, with a group of friends and Melly’s staff. The workshop included the soft sculptures and was facilitated by Savannah and Maike. Since the colors of the sculptures emerged from these workshops, they are dedicated to each participant.

For Maike, the De Kiefhoek publication was very influential for how she wanted to continue to work. According to her, being an artist can be tiring, that’s why for her it is important to make something that feels true to her. “You also don’t want to do works that are very self-involved because they are fun, you also want to place yourself in a context and look critically at yourself and that context. So I ask myself, how do I want to live? It makes sense to me to be able to work with other people, or for instance to support my friends. When I got the Melly show, the first thing I thought was: Ok, now I have money, who can I involve? Who can I share my resources with?”

She shares with the class the fact that when she went to the Master program of Dutch Art Institute, she had to apply three or four times to get in. She came from a very autonomous “hippy” academy, and therefore wanted a more theory-based study. She understands that now those big difficult concepts are taught all over in art academies, and yet she finds they can limit the freedom of movement of artists in such a young stage of their career. But it led her to see that she was a researcher, led her to find feminism, to contextualize herself in a colonial context, etc. So they were all very important steps for her journey.

Takeways on Autonomy

Autonomy in the relationships between bodies, objects and spaces

For Maike Hemmers, “being in relation with…” is an element that is central to her practice because her work is so much based on her own subjective experience, it is very important to find moments to open her practice, so that other experiences can come in. During her presentation, we spoke about autonomy in relation to how we, as subjective beings, are affected by objects and spaces. In her work she explores her own intuitive material relations and those of invited guests who contribute as collaborators or workshop participants. This conversation led Maike to wonder about the autonomy of the objects and the spaces themselves. What does it means to understand something we consider non-living as autonomous? We generally detach desire, movement or agenda from objects and spaces, but they do have these attributes. Maike finds it fascinating “to think about this relationship and mutual influence between subject and object, what it means to understanding something (an object) as having its own world. It’s easier for us with our human perspective to see it in nature, because there is life, and we can see movement and transformation. It connects to topics around ecological autonomy, but also to subject and object. Animals have been treated as objects, women have been treated as objects, people have been treated as objects and these things continue to happen.”